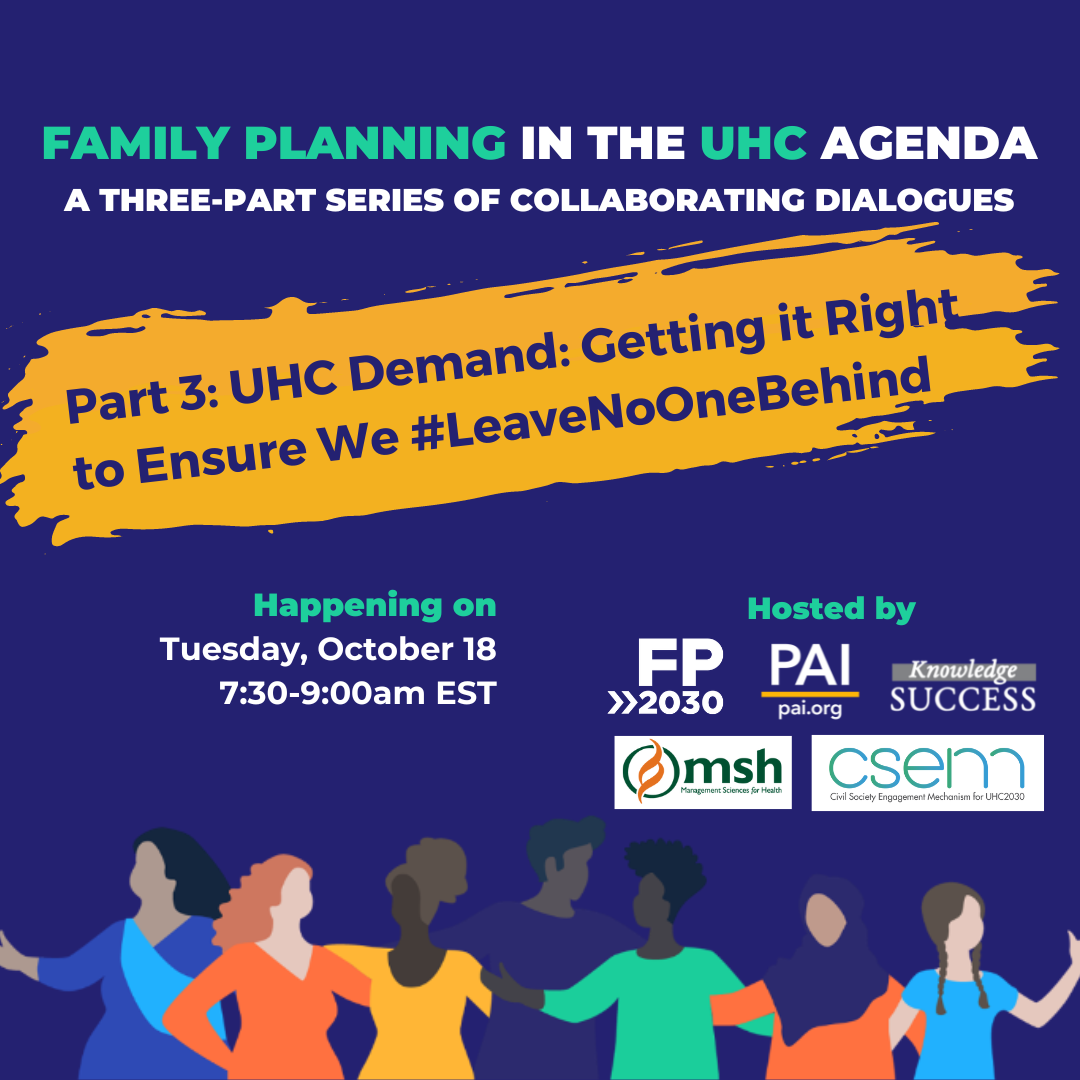

Family Planning in the UHC Agenda, Part 3: UHC Demand: Getting it Right to Ensure We #LeaveNoOneBehind

Knowledge SUCCESS is pleased to offer many webinars and events on relevant and timely topics in FP/RH and knowledge management. This page lists all events that are hosted or co-hosted by Knowledge SUCCESS and our partners.

- This event has passed.

Family Planning in the UHC Agenda, Part 3: UHC Demand: Getting it Right to Ensure We #LeaveNoOneBehind

October 18, 2022 @ 7:30 am - 9:00 am EDT

Start time where you are: Your time zone couldn't be detected. Try reloading the page.

Please join FP2030, Knowledge SUCCESS, and PAI as we host Family Planning in the UHC Agenda, a new collaborative dialogue series to shape policy, programming, and research. Not your typical webinar, this series will bring the family planning community together for interactive discussions in advance of the upcoming International Conference on Family Planning (ICFP) 2022—whose theme is Family Planning and Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

Stay tuned for information on speakers!